I started this research sparked by my friend Local Historian Ann Beedham who was giving a talk on remarkable Sheffielders who have become virtually forgotten. The research isn’t comprehensive but as it is LGBTQ month, I thought I’d let you have a flavour of it.

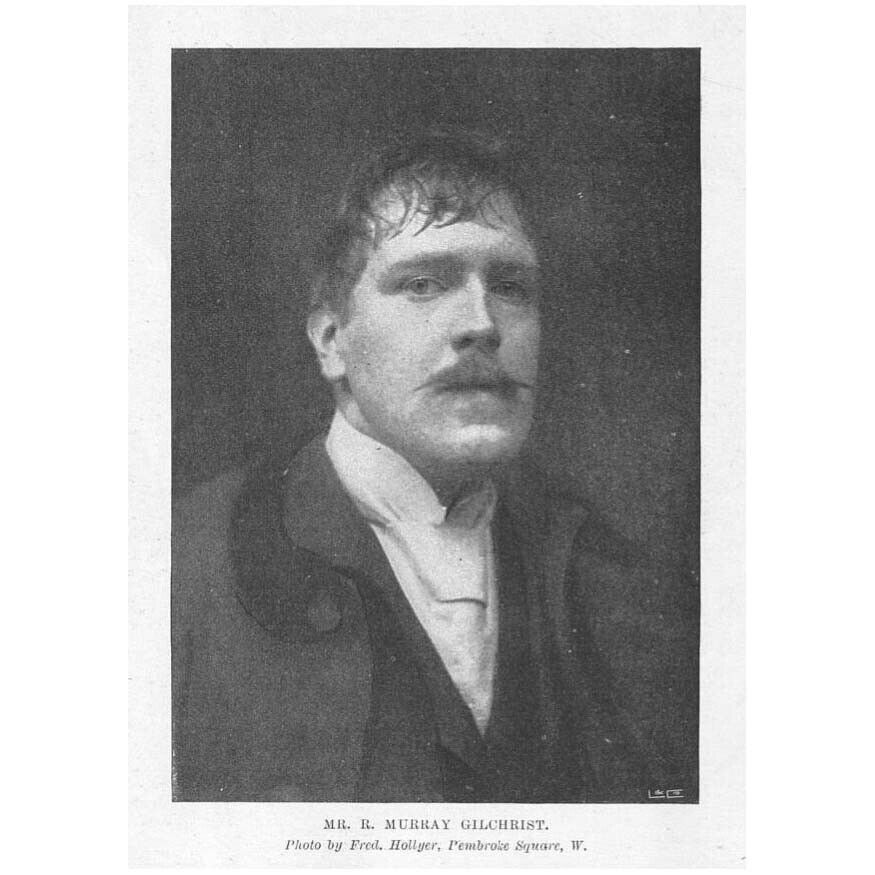

In Holmesfield just outside Sheffield stands Cartledge Hall, once home to Robert Murray Gilchrist, declared by critics “As a ‘rural’ short-story writer he has, in my opinion, no superior among Englishmen.” Yet there is no blue plaque there. His gravestone in the local churchyard makes no mention of his occupation. However, as my research continued, I think perhaps there should be two plaques there, not just one.

First you are probably asking so who was R M Gilchrist? What most biographies seem to miss out is his family background and his childhood.

The Murray Gilchrists family started in a small area of Kircudbrightshire when John Gilchrist married Mary Murray.

In 1832 Mary’s brother Peter Murray, a widower, married Jane Stubbs from Doncaster by special licence in Sheffield and settled in Sheffield. The next year he is mentioned as a Tea Merchant in the Trades Index and over the years added draper to the index and became firmly established in Charles Street Sheffield. Sometime between 1841 and 1851 Peter’s sister Mary and her husband John Gilchrist arrived and set up a tea business in Sheffield too. Their son Robert later known as Robert Murray Gilchrist had been born in Kircudbright in 1834. The Murrays and the Gilchrists created a close-knit Scottish community, founding a Robert Burns club and a curling club. In 1853 Peter Murray was 1 of 18 Sheffielders who got together to create a new Scottish Presbyterian church in Hanover Street. Robert Murray Gilchrist senior besides his work as a travelling draper was making a name for himself as a popular lay preacher. From 1860 onwards he drew crowds to fundraisers across South Yorkshire and Northern Derbyshire. Unfortunately, newspaper accounts don’t say what he preached or how he preached but his popularity lasted at least twenty years.

In 1860 Robert Murray Gilchrist senior married Isabella Murray his cousin, and in 1861 the Murray Gilchrists had their first child Peter. Jane was born in 1864, Robert in 1867, Isabella in 1870 and Alexander Keenan in 1874 and died 14 months later, John was born in 1875 and died in 1878. From the age of eight Gilchrist’s experience was of birth and death, and his isolation must have been added to by his eldest brother emigrating to Australia in 1882

The Murray Gilchrist family was different possibly, but not extraordinary. His mother was said to be a published author, though I haven’t found any book titles with her name on it His two sisters stayed on at school longer than many girls and Jane continued on to take Royal Academy of music exams for the piano to concert pianist level, while Isabella took art lessons at the Art College. The two girls are mentioned entertaining. Isabella singing Mezzo Soprano with Jane on the piano. Jane also gave a musical lecture on the history of music. Gilchrist was said to be a musician too and coupled with his father’s preaching talents, it could be said to be an artistic family. Gilchrist was apprenticed to a relative’s cutlery firm run by Edmund Murray Dickenson after he left the Grammar School. Gilchrist was known as a bright boy, always writing, but on face of it he looked destined for a very ordinary life. Everything changed when Gilchrist reached 21.

When Robert finished his apprenticeship, Gilchrist decided to become a writer fulltime. Here is where my research is a little thin. In another writer’s autobiography he maintained that Gilchrist started by submitting children’s stories to “Young Folk’s Papers”. The magazine was aimed at older children and young adults and to encourage young unknown writers. It is known that Gilchrist started a correspondence with the Editor William Sharp, but not whether he was published at that time. Sharp, ten years older than Gilchrist ,was enthusiastic about Gilchrist’s talent and he went on to form a strong friendship with Gilchrist and Gilchrist’s partner George.

I know Gilchrist did write for children. Many famous writers including Robert Louis Stephenson started in the Young People’s Papers, as the rise in children’s literacy pushed up demand for appropriate reading material. So perhaps he was already being published when he took the momentous decision to give up his work at his cousin’s Cutlery factory and become a writer fulltime and write his first novel?

1890 would seem to have been a momentous year for Gilchrist, his first novel Passion the Plaything. was published, and he and George Garfitt, who became his life partner, moved to a farm cottage outside Eyam. Garfitt’s sister had married the year before and his mother had given charge of the business to him and his brother Charles.

Gilchrist was only 23 when his first novel Passion and Plaything (1890) was published to mixed reviews. Some praised its ‘hauntingly beautiful prose’ but the Spectator voiced reservations: ‘It is an almost delirious story of passion which in ordinary life would end in hysteria or madness, suicide or murder. The author is not devoid of literary prowess, but altogether this is an unpleasant book containing far too much in the way of sensuous description.’ So, what was to continue for much of his life a strange collection of reviews that loved his attention to detail and descriptiveness but not sure about his sense of the macabre yet drawn to it. Although he is often described as a gothic horror writer or a writer of the weird, Gilchrist had a unique style difficult to describe exactly.

“ Gilchrist divided opinion – he introduced themes considered controversial and even taboo by much of Victorian society. Gender lines were blurred, traditional roles of hero and heroine reversed, and the rising feminist cause ardently espoused. One of his characters was almost shockingly unthinkable – a female serial killer. Several stories featured same-sex desire” Peter Seddon Great British Life 20th April 2015

The couple set up home at Highcliffe Nook, near the crest of Sir William Hill (now topped with a tall communications mast), high above Eyam. The Nook, a lane, runs from Hawkhill Road, up the steep hill to Highcliffe Farm and Highcliffe Hall, from which there is an extensive view. Some of his best novels are centred in Eyam, which he called Milton. Garfitt found a passion there for studying the stone circle and other ancient stones.

“Eyam Moor has none of the depressing grandeur of the Kinderscout region; its beauty is softer and more ingratiating. A place to walk over in the still hours of a summer’s night, when the grey paths are only faintly visible, and there is no sound save the whirring of the goatsucker’s wings. And at dawn one hears the cold singing of the larks overhead, as they welcome the rising sun, as yet unseen by mortal folk. Of an evening too, in winter, one sees the clouds gathering over the uplands of Middleton Moor, like goblins making their way towards some monstrous ark” The Peak district by RM Gilchrist .

It is generally agreed that Eyam became the inspiration for many of Gilchrist’s stories, often written in the Derbyshire Dialect, as well as being a source of delight to Gilchrist for his love of hiking and the natural beauty of Derbyshire. Not all his stories were in Derbyshire, but were for the most part set in the north of England, such as Cumberland or Lancashire.

It is likely that the Garfitt and the Murray Gilchrist family were well acquainted. Garfitt’s parents were devout Wesleyan Methodists as was Robert Murray Gilchrist senior. In Heeley where Garfitt and most of the family were born, the family had strong links to the local Methodist Church founded by among others Garfitt’s grandfather. Garfitt’s father Thomas unfortunately died in 1878, and a year later Garfitt’s brother Thomas died at the age of 19 and his mother took over the running of the company, Thomas Garfitt & Sons. At 16 Garfitt became a trainee clerk there. It was not unusual for wives to take over when their husband died though their name rarely features in the trade directories. The Cross-scythe works, as it was called employed 20 men and six boys and made scythes sickles and knives. The company also spread across several continents with the firm having permanent representation in Paris. The firm obviously kept its international reputation as two years later under his mother’s control the firm won a gold medal for their wares at the Sydney Exhibition in Australia.

As Garfitt grew older he travelled quite extensively for the business, visiting, for example, Hamburg, Copenhagen, Calais, Paris, and Cork. On these journeys he wrote regularly to Gilchrist. From the Victoria Hotel in Kilkenny in April 1898 he wrote: “I think constantly and tenderly of you and my thoughts always turn to you”, though at the same time he lamented: “It seems an age since I had a letter from you”.

I have found no physical description of Garfitt. Gilchrist apparently was a hard man to miss. The novelist and friend, William Kineton Parkes recalled meeting him at Axe Edge, six miles from Buxton, on the way into North Staffordshire, “a great figure in Scottish tweeds came towards me over the moor; striding in knickerbockers, hat in hand, revealing the finest forehead I have ever seen; a lock of auburn hair drawn over it to qualify its wonderful height; the biggest and gentlest man I have ever known”. (The Bookman, May 1917)

A notebook, with a sermon used as a cover, in the Sheffield Archives gives a glimpse of how he created his stories. It is like a word sketchbook where he would jot down descriptions of a building or a character. Here is his description of the house in Eyam.

The Nook in a November Twilight

Inexpressibly eerie lay the tall highly chevroned house, against the background of gaunt, leafless sycamores and sky of crystal-green-citron. The rippling mumbling of the two springs the only sound; the light in the house-place window the only sign of life. Frozen snow lay thinly on the over- grass-grown road.

In 1892 Gilchrist submitted stories to “The National Observer” which increased his readership and gave him a mentor and gentle critic, the editor, W E Henley. Gilchrist’s story were printed alongside other famous authors such as Yeats, and H G Wells. Later, fans of Gilchrist’s work would relate how they scanned each edition eagerly searching for Gilchrist’s contribution.

In the same year Gilchrist also sent a story The Noble Courtesan to Sharp for his magazine the Pagan Review. Sharpe said he thought the woman in the story should be more mysterious and less evil. The magazine had to be cancelled due to Sharp’s ill health, but Sharpe found Gilchrist’s review of it in The Library and was pleased by it, and, Sharp wrote, he would look to Gilchrist “as one of the younger men of notable talent to give a helping hand”.

In 1893 Gilchrist brought out 4 more stories for the National Observer, and another novel. All this while on a personal level life was getting busier elsewhere, as Garfitt and his brother Charles took over management of the family firm in 1891, and Garfitt had to go to Paris to represent his company at the Agricultural Fair there. It is suggested by some researchers that about that time Gilchrist was in Paris. Rather than be parted, did he join Garfitt in Paris? Sharp had suggested Gilchrist and Garfitt visit him at his home that year but instead he visited them in September at Eyam, and they visited him the following year. Gilchrist helped Sharpe find a publisher in Derby who would publish Shape’s books under his pen name Fiona MacLeod which Sharpe wanted to do so as to explore his feminine side. As Sharpe told a friend “Don’t despise me when I say that in some ways, I am more a woman than a man.” Through Sharpe and other literary friends Gilchrist and Garfitt made friend with others who were Gay or were happy to accept them as they were.

It was in 1894 that Gilchrist produced the book the Stone Dragon which critics agreed was his best work so far, and was a sign of his maturity as a writer.

“The book is sinister, enveloped in gloom — yes, and Decadent (like much fine literature): but it is strong, it has authenticity; the effect sought is the effect won. There is nothing quite like The Stone Dragon in modern English fiction.”

Gilchrist dedicated his book to Garfitt and many experts when they came to review the books in recent times have commented on his short piece “My Friend” prompting them to remark without knowing anything about Gilchrist that he was “possibly homosexual?” But what did his fans and critics think at that time? Being homosexual was not legally acceptable. It was only in 1828 that the death penalty had been removed. And in the spring of 1895 the most famous or infamous trial of Oscar Wilde exploded into the papers. With his conviction and imprisonment for acts of gross indecency, how must that have impacted on Gilchrist and other Gay writers? Although public attitudes grew suspicious and aggressive to same sex relationships, there is no indication that anyone felt that way locally in Sheffield or Derbyshire. People always spoke warmly of Gilchrist

“Always moderate of habit – the only writer to regularly contribute to the Abstainer’s Advocate the journal of the Temperance Movement – he was a big handsome presence with a stately grace, who had the same word of welcome for both rich and poor. Dazzlingly eccentric and something of a country dandy, he favoured brightly-coloured clothes, and periodically turned up in church wearing a cassock and girdle. We shall remember him as a man of quiet charm, a soft-spoken companion among his pipes and books.’

In 1895 the couple came to a new arrangement and together with Gilchrist’s parents and sisters rented the two sections of Cartledge Hall in Holmesfield. The two wings were independent of each other and declared separate households in the 1901 census. Why they left their beloved Eyam is unknown. Perhaps to make things easier for Garfitt’s work, or that Garfitt’s many trips abroad often left Gilchrist feeling isolated and lonely. Whether they joined together for meals or to entertain Gilchrist’s guests is also unknown, but several of Gilchrist’s author friends mention Gilchrist’s mother Possibly it was a suggestion by Edward Carpenter, the socialist poet and Gay activist, who lived in nearby Millthorpe with his longtime partner George Merrill? Merrill was always registered as a servant in census returns. Garfitt was not, as apart from anything, given his high position in Thomas Garfitt & Sons that would have been stretching credulity too far. In 1901 census he is put as a visitor but in 1911 he is put as a boarder. I am unsure what the quiet living couple would make of Edward Carpenter, though pretty sure Merrill with his hard drinking would be difficult for a couple strong on Temperance.

Another admirer was the writer Hugh Walpole, who was visited by Gilchrist on one of his rare visits to London. Walpole visited Cartledge Hall several times. “The house was all that the most romantic novelist could desire; its rooms were so low that you must be for ever bending your head, thickly beamed & quite incredibly dark. […]. So dark was the house that we lived for most of the day by candle-light. Gilchrist preferred it that way. Out of doors he would walk mile upon mile with a giant stride and couldn’t have enough of the sun, wind and air; indoors he liked candles and Elizabethan thickness of atmosphere and, if possible, the rain beating on the leaded panes”. “I think that my youth provides no more charming memory than of this big-limbed broad-shouldered man gently reading one of his richly fantastic stories in the candlelight while, beyond the windows, the storm swept the moor and the rain hissed down the chimney.”

In Rue Bargain Gilchrist uses a description of Cartledge Hall. “A squat, rambling manor at the end of a well- wooded village. The furniture dated from the last century. The rooms were large and low pitched, panelled with unpolished English oak, all diapered in satin veinings; the ceilings were of ornate Elizabethan plaster work”.

Moving to Cartledge certainly didn’t slow Murray Gilchrist down. He increased his magazine contributions to a wide range of publications but was also often bringing out two books a year. Gilchrist was described as a methodically writer who rarely took time away from his writing.

Suddenly in 1901 uncharacteristically Gilchrist stopped and no new writing appeared. Not because he was losing popularity. His latest which came out in 1900 “The Courtesy Dame” was getting rave revues. Both from friends.

“I owe you a letter since-how long? I had a rather not try to calculate. But I know its an inconsumable time, for the thought of it has more than once been with me in the watches of the night.

I read the Courtesy Dame – (this, after all, is what I wanted to say). – ‘with very great pleasure. It has character and atmosphere, and is excellently written. You are going steadily up and up; & tis not without a sense of pride that I watch your ascending. I remember how I backed you long ago, & I rejoice to know I was justified in you, as in so many more.” 1901 W E Henley

And in the Press

The Courtesy Dame

By R. Murray Gilchrist

Literature “It possesses all the sweetness and rusticity of a pastoral, but through it a thousand lights and shades of human passion are seen to play. The story will immediately grip the reader and hold him until he reaches the last chapter.” The Morning Post – Mr Murray Gilchrist is an artist to the point of his pen, whose story is at once amongst the freshest and sweetest of recent essays in imaginative writing.

A clue to this sudden gap may be that Garfitt’s mother died in the June of 1901. Gilchrist’s short stories were now syndicated across the country, and beyond, with stories being printed in many local weekly newspapers. The papers proudly announcing they had the latest Murray Gilchrist story printed in its entirety and their readers would be the first to read it, as if the story had been newly written, which was not always so. Perhaps it was Gilchrist’s popularity with the ordinary people that led some critics to undervalue his work. The writer and critic, Arnold Bennet, had no doubts about Gilchrist’s talents. A book he sent to Gilchrist is inscribed: “To Murray Gilchrist, author of some of the finest short stories in the English language. From one who holds very strong opinions on literary questions, & believes in them with his whole soul. E.A.B.”.

While Gilchrist’s career was definitely in the ascendant, Garfitt’s business was hitting obstacles not of his making. In 1905 unrest and nationwide strikes in Russia meant that one of the companies’ biggest customers, the Russian government was not paying their bills and Garfitt asked the Foreign Office to intervene, but their reply was far from helpful. In 1906 the works caught fire and the majority of the works was gutted. The damage was said to amount to several hundred pounds. The works were insured but it could not have happened at a worse time.

Around 1906 Garfitt decided to buy a car. Gilchrist also wrote a mystery crime novel called the Abbey Mystery in which a car goes up in flames. Whether that was something he saw or from his imagination I doubt we will ever know. The car enabled them to explore the country more easily. Gilchrist was commissioned to write some guidebooks. His first was understandably the Peak District.

In 1912 Garfitt was elected to the Sheffield Trade of Commerce and in same year joined membership of the Royal anthropological society. The Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland (RAI) is the world’s longest-established scholarly association dedicated to the furtherance of anthropology (the study of humankind) in its broadest and most inclusive sense. Garfitt also joined the Hunter Archaeological Society in Sheffield, which was formed in 1912, and named after the antiquarian Joseph Hunter, the stated aim of the society was “To…record all antiquities discovered in the progress of public works”, and to collect information in general that “require more thorough examination by systematic scientific investigation” In 1913 Garfitt is to be found helping fundraise for an exploration of the Templeborough Roman site (Now Magna) He wrote an article in 1914 for Hunter’s Archaeological society called Castle Hill in which he argued that many of the mounds that Norman built their castles on may have been made much earlier. It is one of the few pieces of writing I have found but it indicates a well-educated man, capable of researching literature and confident enough to make his own assertions. In 1916 he was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Anthropological Institute, a section of the British

At the same time Gilchrist was visiting places to write his guides, the Dukeries in 1913, Scarborough and Neighbourhood in 1914. He obviously wasn’t impressed with Filey as he described Filey as ‘rigid and inhospitable, cold virgin to Scarborough’s countess in his notes . Gilchrist was slowing down. His large frame was causing him pain in the shape of what he called his “rheumatism”.

His main obsession became the Belgium refugees, and he spent a lot of time learning about their lives in Belgium and their culture and their love of waffles. In 1915 he wrote an article for the Sheffield Telegraph “Belgium Guests, some Characters”. It was said that he had completed a book on Belgium lives and culture, but it doesn’t appear to have ever been published.

He also wrote an article in the Telegraph of a walk to Smeekley wood and beyond, in June 1916. Quite possibly a walk he had often made. There is possibly a wistfulness there in the writing but Gilchrist was often wistful.

Just before Christmas in 1916 Gilchrist’s father died. For a man who had lived for 82 years his obituary said very little.

In February 1917 Gilchrist’s latest book was released “Honeysuckle Rogue.” It was described as

“ A delightful story, delightfully told. It carries you right into the heart of Rural England, there to become a privileged spectator of a charming romance. A typically English tale, to read it is almost as good as holiday.” The Daily Telegraph February 23rd 1917

On Sunday 28th of February 1917 Gilchrist took ill with a chill, and made a bed in the dining room as the bedroom was too cold. Pneumonia set in. By eight pm on the Wednesday, he was dead. The obituaries say he died of a heart attack. The Obituaries were long, and from far and wide. It must have been especially hard for Garfitt with the significance of their long relationship together of nearly 30 years not able to be mentioned. Did people know and choose to ignore it, or did the two sober hardworking sons of Godfearing fathers just not fit with people’s stereotypical view of a Gay couple? Eden Philpotts , a close literary friend wrote a memorial poem part of which is quoted here, with echoes of a poem by Lord Alfred Douglas, Oscar Wilde’s lover, which had as its last line “The love that dare not speak its name

Work ended and the bells have chimed their perfect

Chime

To him the splendour worthy of his pains.

With death, the shadow of a purple cloud,

And love, to speak his living name aloud

While beauty hand in hand with righteousness still reigns.

After the funeral Garfitt went back to Cartledge Hall and carried on his work at the works, and his increasing involvement in archaeology. Gilchrist’s sister gave readings of her brother’s short stories and some obscure local newspapers continued printing Gilchrist’s short stories.

Gilchrist, in his 27+ years of writing had 30 books published and over 100 short stories plus many non-fictional articles. His work was well known by everybody who read a weekly local paper. His last book went into several reprints in the first few weeks of it being published, so why is he so little known now even locally?

Let us also ask why Garfitt is dismissed by many who have written a Biopic of Gilchrist’s life? Apart from the fact that he was Gilchrist’s support all Gilchrist’s literary career. It was suggested that Garfitt and Gilchrist might have met when both apprentices, which is hardly likely since when Garfitt was junior clerk at the age of 16, Gilchrist was still a pupil at the Grammar School. No one has examined Garfitt’s educational background. He was obviously educated but self-educated or did he gain a scholarship to the Grammar School like Gilchrist?

In 1919 Garfitt and his brother Charles sold the company which freed Charles to move to the Isle of Wight with his family, and Garfitt to concentrate on his archaeology. For the first time, since Garfitt was 16, he was free of all family obligations.

In 1920 Garfitt returned to his first enthusiasm which developed when he and Gilchrist lived in Eyam and gave a lecture at the Hunter’s Archaeological Society on stones which were thought to have carvings on and his thoughts that the stone circles were of a much earlier date than was currently thought. More recently the carvings he cited on two Eyam stones is now thought to be natural weathering but the latter has turned out to be true. That same year he was a member of the Hunter’s Archaeological Society committee investigating the Templeborough site.

In 1921 a work man blasting for Blue John found an ancient skeleton in a cave near Castleton. Garfitt was excited. It was a place he and Gilchrist knew well.

“Of old the only way of crossing was by the “Winnats”, a romantic pass that starts impressively but soon becomes dull and uninteresting.” The Peak District, R. M. Gilchrist.

Garfitt and Leslie Armstrong were appointed by the British to investigate the site and rock fissures and caves in Derbyshire generally.

In June his brother died and once again he was facing family obligations. Charles left £12,619 15s 10d to his widow and his brother. In 1922 Garfitt married his brother’s widow and moved to the Isle of Wight. Garfitt was 60 years old. He can’t have spent much time there, judging by the work he became involved in back in Sheffield and elsewhere.

Throughout the years from 1920 – 1926 Garfitt was partnering Leslie Armstrong in investigating the caves near Castleton and the caves at Cresswell Crags. But in 1924 Garfitt chaired a conference in Toronto on the origin of Copper working. It is his work on this that was to gain the most recognition and praise from his fellow historians.

The idea was to collect copper ore samples from known old copper mine workings in Africa and Egypt and establish their unique structures and compare them with the crystalline structure of ancient artefacts and look for possible common source. For an ex-steel manufacturing owner of an international company this was work Garfitt was especially suited to. He had both expert knowledge and the contacts overseas.

In partnership especially with Harold Peake they organized work on early metallurgy based largely on spectroscopic and chemical analysis of minute borings of ancient implements. This work led to an increased knowledge of early sources of metallic ores, technical processes, and lines of trade. He not only organised ore samples and artefacts for Professor Desch to analyse he even travelled to Mozambique in 1929 to chair a conference there. Peake comments in his Presidential address that the acclaim should be going to others, especially the secretary, Mr G. A. Garfitt, “to whose untiring energy is due the work that has been accomplished.”

Garfitt continued his involvement both locally, in working with Leslie Armstrong to record the remains and what artefacts were appearing when building commenced on the Sheffield Castle Site in 1929, and coordinating with the investigation of the Kent Caverns near Torquay, as well as all the copper research till the day he died. His obituary in the Daily Independent headlines it as Mr. G. A Garfitt, Well Known Sheffield Business Man Dies. It goes on to say.

“The death has occurred at Ryde, Isle of Wight, of Mr. George Alfred Garfitt, a member of an old Sheffield family and a well-known man in Sheffield.

Mr Garfitt was head of the firm of Thomas Garfitt & Sons, of Highfield, Sheffield, a business which was established in the 18th century, and up to about 12 years he lived in Sheffield and was a well known figure.

He was a member of the Sheffield Reform Club and took a keen interest in archaeology. He was also a member of the British Association and at one time was chairman of one of the sections of the association.

Although he went to live in the Isle of Wight when he retired, he visited Sheffield from time to time”

No mention of a wife, or his living for 28 year in Cartledge Hall or Robert Murray Gilchrist.

Further reading

Here are some links to Gilchrist’s writings.

https://archive.org/details/gilchristthestonedragon1894

Short stories and articles can be found by using https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/ (pay to view but can download several at same time)

Garfitt has 2 articles that can be found within the Hunter Archaeological Society publications in Sheffield Archives.